My words are waterlogged. Too long in a world I’m only meant to be in for a short while.

When my son died, words flowed out like snowmelt waterfalls. More questions than answers. Trying to make sense, work it out on the page. A shunting of the grief. Now, words pool at my borders. Stuck there. Too much to be said. No words for any of it.

They both became skeletons in their skin, my dad and my grandmother. The slow starvation of dying.

My grandma was a turtle in her turtleneck on her death bed. It was early October when I walked into her room and said, “You’re ready for Christmas!” because I didn’t know what else to say after our foreign intimacy: hospital bed greeting of side-hug and bungled kiss on the cheek. After “Oooh, I’m so sorry you had to come all this way!” After, when even with people who have been our people since before we were born, there is an awkward silence. There is a death bed between us.

“Whaaat?,” she said in her I-didn’t-hear-you-voice. Not her astonished “what?!.” Not her I-don’t-understand-you “what.” This one is breathier. It’s drawn out.

“Candy canes,” I smiled and pointed to her shirt.

“Oh yes!” she laughed as she looked down in slow motion, took a a few too many beats to register the red-on-white pattern, and more still to run her fingers, bones Saran-wrapped in skin, over the thin, textured, bleached-out hospital blanket. Wiping it clean of its wrinkles. Like when she used to tug at the edges of the placemats on her kitchen table before lining up their edge to the table edge and then tapping its center with four of her full-figured fingers, an approval of orderliness. Like that, but slow. And decades later. And dying.

The skin on her neck was long drapes of fabric, sinking into her collar. A mock turtle neck. She’d close one eye, turn her head to one side and then jut it out to try to get a glimpse of the loud roommate behind the temporary divider. My daughter and I would share a laugh with our eyes and stifle a real one. She looked like a turtle, shifting its little head from its shell on its spindly neck, ready to locate its leafy prey. We’d laugh at our mock turtle Gram. Our dying Gram.

Later, she would exclaim, “I outlived the queen!” and purse her lips in her whadda-ya-think-of-that face. And she did. They were the same age: 96. My daughter had said the same thing on the plane, as we flew across country, hours after hearing of her heart attack and return to her assisted living for comfort care. “Gram outlived the queen!”

“She sure did,” I said.

“You sure did,” I said.

My dad’s handlebar mustache was now wider than his smile. “Bring the grooming kit,” he texted from the CV-ICU, “This thing is bothering me.” Nothing should bother him so my aunt cut it off with dull nail scissors, which was all I could find. There must have been a grooming kit in one of his bathrooms but I scoured and couldn’t find it. You can’t always see what’s right in front of you, especially at times like these.

A few days earlier on the phone, I’d said, “It’s called wasting, Papa,” foolishly trying to educate him from 2,807 miles away, “You have to eat.” He wasn’t hungry. He’d lost a lot of his taste in the past 6 or 8 months, maybe a year even. “Half a yogurt on Thursday,” he said, like he was proving me wrong on Saturday.

You can’t know if he’s dying through the phone. But then my cousin called and said, “He looks like Gram did and not because of the resemblance.” Honestly, you have to hit me over the head to see it, right there, in front of me.

He’d been looking like her for months, maybe over a year. Every time I’d bought him a shirt for a present in the last few years, it had been a size too big. Not four months ago at Christmas, he’d repeated again, “That’s okay. It can be a night shirt.” You have to hit me over the head but also there is a room in my mind, maybe a closet, maybe a hallway, where a light does come on. When I hear “not because of the resemblance” I know she means he looks like she looked five months earlier, when she was dying. But I turn that light off quick. Five to ten years the doctor had said, not even a year and a half ago. Switch flipped. Hope is more real than the evidence before me.

“It’s called wasting, Papa. Your body goes from eating fat to eating muscle. You have to eat.”

“Okay,” he said, “send me the protein powder.”

I also sent him a 90 day supply of multivitamins. How are you supposed to know he is dying over the phone? There aren’t even cords or wires connecting us anymore. Just frequency. Just air. Nothing, really.

The day before we left to return to Portland, she was so deeply asleep I couldn’t wake her. A tortoise without her shell. A shriveled body of my Gram. Just yesterday, she was asking about my daughter’s cross country team, remembered her dad had gotten married last spring and asked how the wedding was. She was in and out those last few days. Awake and then asleep and then awake again, saying several times with a start, “Am I still I alive?!” My daughter and I, laughing with our eyes and our voices, would say, “Yes, Gram, you’re still alive.”

I began to wonder where she went when she was asleep. She seemed to be farther away than a regular nap, than a normal night’s sleep even. Her breathing became more labored. Her mouth slack and open. The chapstick and mouth swabs abandoned on the rolling tray table next to her adjustable bed. If she was more alive, she would have been snoring. But no, this was the laboring of dying. This was the being born into the next world.

We sat there together, my dad and stepmom, my daughter and I, and I put my hand on her hand and we watched her, not saying anything to each other or to her. The spaces between not breathing at all and then taking a breath lengthening. Once she didn’t inhale for so long, I thought maybe that was it, her last breath. I nodded to my dad who sat forward in his chair, my daughter’s eyes widened and I could almost feel the clenching in her chest in mine. But my Gram gasped again and we settled back in, my daughter telling me later that she was terrified she’d die while we sat there. I said, “I understand. It’s scary. But I was hoping she would. I don’t want her to die alone.” And she said, “Yeah, but I didn’t want her to die when we were with her either.” Me, either. Both.

My dad called dozens of people. In the slurred speech of the old, the sick, the dying, he said “Goodbye” at the end. Like you do when you end every phone call. Except these were weighted. Over the few days of calls, he honed his craft. If the person on the other end was choked up, if it was awkward and hard, he’d switch to “I’ll see you on the other side.” and somehow that would free them to say, “Okay, goodbye, Rick.” It was miraculous.

On one of the first days when he was making calls, I walked in to his hospital room and started tidying, plugging in gadgets, asking for the doctor. To the wife of his best friend from growing up he said, “Hi Margaret,” with a pause for when she surely said, “Hi Rick, how are you?”, he said, “Well, I’m dying.” Another, longer pause and then “No, I’m not kidding.” and then she clearly and quickly went to get her husband. When he hung up, I said, “Maybe you should ease in a little,” and we laughed.

After that, he became a pro at his goodbyes, at his dying. It was one of the most incredible and beautiful things I will ever see. Person after person: how much he loved them, reminisces and laughter, apologies now and then like sprinkles on ice cream and then a pause for the truest and most real goodbye they’d ever said. “Until we meet agin.” Just listening, I have never felt so alive as an essential part of me lay dying.

I left my Gram there. On her death bed to die, alone. The nurse came in to give her morphine that last day and I’d hoped that that would rouse her. It did not. She moaned a little as the mechanical bed jutted into motion, her head a little further back so the nurse could syringe the medicine into her gums. She went back to her breathing/not breathing, her living/dying, relatively uninterrupted.

My dad said “Okay.” In his way that means, I’m done so we’re all done. It’s a tone I’ve seemingly always known.

“Okay,” I said in the reluctant tone I always make in agreement.

They said their goodbyes. My daughter, tentatively touching her great grandma’s now tiny hand. “Bye, Gram,” she whispered and joined her Nona and Papa in the hallway.

I looked at my grandma, one of my best friends in this life, my champion and advocate, my safe harbor in the storm of me early years, the one who said “You’re moving to Cortland?” a town not 40 minutes away, when I told her I was moving to Portland, nearly 3,000 miles away. The one who compared her opening a store in Binghamton, a small city not 15 minutes from her house, to my cross-country uprooting. The one who had dishes of hard candy with soft centers wrapped in foil that made them look like strawberries. The one who let me push the buttons on the cash register at her store and made me cups of hot cocoa from envelopes of powder in styrofoam cups and hot water brewed in her mini coffee machine. The one who sat with me for hours over tea at her kitchen table, sharing her life with me and mine with her, taking me seriously at every turn of my adolescence and young adulthood. The one who picked me and my cousin up late every August and gave as each 100 whole dollars to buy back-to-school clothes. The one who taught me to fear and respect money and its inevitable loss and perpetual, potential gain. The one laying there, chin up, mouth agape, dark hair finally graying beyond the temples, wrinkled turtle skin along her brow, around her eyes, rippling out from her mouth. The one here for just shy of 97 years. The one.

I leaned over and said, “I love you, Gram,” not able to add a goodbye (I still had a few months before my dad would teach me how). I kissed her forehead, something I am sure she had done to me countless times when I was younger and shorter than her but that I had never done to her. I wanted there to be more than this.

She woke a little, irritated by what she thought was another interruption by yet another nurse. I said “It’s okay, Gram. It’s me, Monica.” And as she fell back away from me, fell back away from this life and this world, she relaxed into the sigh of delight she gave each time I called her and announced myself, each time she received good news. It’s an “oooooh” of a young girl, born in her childhood, I imagine, when given a rare sweet by her mother. Perhaps it’s a sigh she learned from her mother, dead when my Gram was just 13. It is the sound incarnate of pride and joy. It trailed off with her to wherever she went next.

My dad went and sat with her the next night. The autumn sun had set. She never woke. He sat next to his mom, just 18 years his senior. His own withering well on its way. Our collective family sigh of relief that she would die before him, not suffer one more loss in a life full of them. Like all full lives.

He sat with her and he put his hands on hers. He told me later, “I just sat there quietly with her. I didn’t say a word. I held her hand and I counted her breaths. And, you know, there was a rhythm to it. About 30 seconds breathing and about a minute without.”

In that image, I saw this: A young woman, her husband at war, her new baby in her arms, almost exactly 77 years from that very night, not 20 minutes from where they sat now. She held her little boy, rocking him in the night, putting one of her fingers in the way of his fist so he might hold on to it. As he fell asleep in her arms, she rocked him and counted his breaths, waiting for their rhythm to develop, waiting for him to be far enough away in sleep that she could lay him in his crib and tuck her own, tired self into bed. Their lives together only just beginning. Never imagining this inverse. Never imagining how he would comfort her at her end.

She died a small handful of hours later.

The last place and the only place I wanted to be was sitting alone with my dad in the blue-light illuminated hospital room. The last place and the only place I wanted to be was watching my father labor. His chin up, his moth agape, what was left of his musculature laboring for breath, the crinkle-fabric skin tightening around his clavicle with each exertion of an inhale. I wished to be anywhere else in the world and I couldn’t imagine not being there with him, sitting with him, keeping him company, hoping he knew I was there. Tentatively putting my hand over his, afraid to disturb this process, this last hard work. His hand was cold, his heart slowing the push of warm blood so that it no longer reaches his hands or feet, not even his shins or forearms by then. I had to touch them. To make sure this was real. Really happening. Feel it for myself.

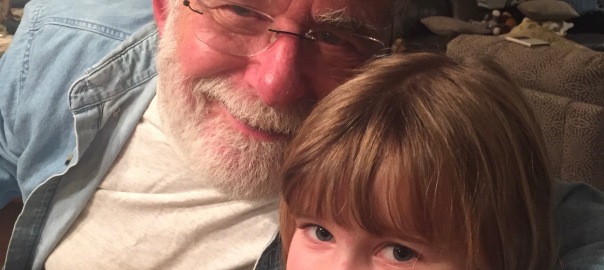

I curled my fingers around his thin palm and I tried to count his breaths. No rhythm emerged. No sense was made. No beautiful allegory except that before he fell into his morphine coma, he had told me, again, about going to sit with Gram that night. And the day before that he had looked at me, one side of his mouth retreating to keep the tears at bay and said “You and I are like Gram and me.” I wished I had smiled a little and nodded and said “We sure are.” But instead, I wrinkled my brow and cocked my head and said “Really?,” not finding the longevity in us, not the proximity, missing the connection.

“Mhmm.” he nodded. “We are,” having to convince me but being too tired to, too dying. Having had to convince of too many things for too many years. Always met with my dismissal, my cynicism. Until weeks or month or years would pass and I”d come back around and tell it to him like it was my idea. Eventually, he told me “I just quit saying ‘I told you so’,” and then leaning back in his chair crossing his arms over his chest, above his then-belly, lifting his eye brows in interest and curiosity, he said, “Now I just do this and say, ‘Oh really? Great idea!’ and then you explain it to me more!,” And we laughed, even me, because it was true.

We are. My dad and me, my Gram and him. Right there in front of me.

So I sat with his efforted, asynchronized breathing and I pulled out my phone and started writing his obituary. I sat with him and began to tell the story of his life. One milestone at a time, one achievement after another. The way he loved this life and lived it enthusiastically. The way he tried to teach me to do as well. To overcome the foreignness of my bittersweet nature he thought maybe he could parent out of me. I wrote the words his friends and family would read, old acquaintances or colleagues might stumble upon, a genealogical researcher might go looking for. While he did the work of leaving his body, I began to write about him in the past tense.

He died a small handful of hours later.

Here are the words. I am lighter now. My body resorbing the excess. And then you, taking some of it in for me. Perhaps, finding your story in these watery words. Hopefully, though, by the time they reach you, they are gaseous. Just air.